We recognize the following limits on the types of human memory:

– The working memory holds 7 +/- 2 entities

– The short-term memory can have substantial capacity, but knowledge there declines after six months to a year without reinforcement

– The long-term memory can hold things for a long time, but even this declines after several years without reinforcement

– Knowledge moves from working to short-term to long-term memory at a fairly slow rate, on the order of thousands of entities (which could be quite complex, since they can build on previous knowledge) per year.

– Asking people to perform simple tasks such as basic arithmetic result in error rates that can be anywhere from 99.9% to 50-60%, depending on the person’s skill and time allotted for the task.

As such, when we ask people to perform knowledge tasks, we need to understand what we can really ask them to do:

– We can’t ask them to make calculations with 10 or more significant factors without mental aids, computers, and and/or learning time to be able to transition the factors into more complex concepts

– When we ask people to switch to a new task requiring independent work using a decent chunk of new knowledge, we have to expect a ramp-up time measured in weeks or months to allow the new concepts to enter short-term memory

– When we ask people to do something highly intellectually demanding, and which builds on complex concepts, we have to plan for it years in advance, to allow them to absorb enough knowledge into their long-term memory so that they can manipulate those complex entities without having to rely on short-term and working memory for most of the work.

– When we reassign people from tasks, we should plan for them to lose their most specialized and temporary/provisional knowledge in six months to a year. Further, if we reassign people away from their specialty for years at a time, we have to budget for time to replace the lost long-term memory, if we once again require that level of expertise.

If we fail to account for these things, we are ignoring obstacles just as obstinate as any physical challenge.

Physically, we recognize that there are tradeoffs between muscle, fat, speed, power, endurance/stamina, and size, and that it takes months for the effects of differing diet and types of exercise to effect a switch between a given choice among these factors. Furthermore, under severe physical strain, people’s joints break down, become painful, and ultimately useless. Consequently, we have to expect that only young, strong people can take on some of the most demanding physical challenges, such as service in the infantry, without long-term damage. Even using physically fit people may cause them long-term health problems, since joint damage and lingering effects may not manifest until their muscles and strength begin to physically decline, putting additional stress on the joints, and wearing out the remainder of their organs’ capacity, e.g. kidney failure. We can measure people’s strength and build them up on a case-by-case basis, but predicting the end-state physical capacity is hard; even professional sports scouts can’t achieve a very high accuracy. Consequently, we have to design physical tasks to be well below the maximum for the personnel that we expect to assign.

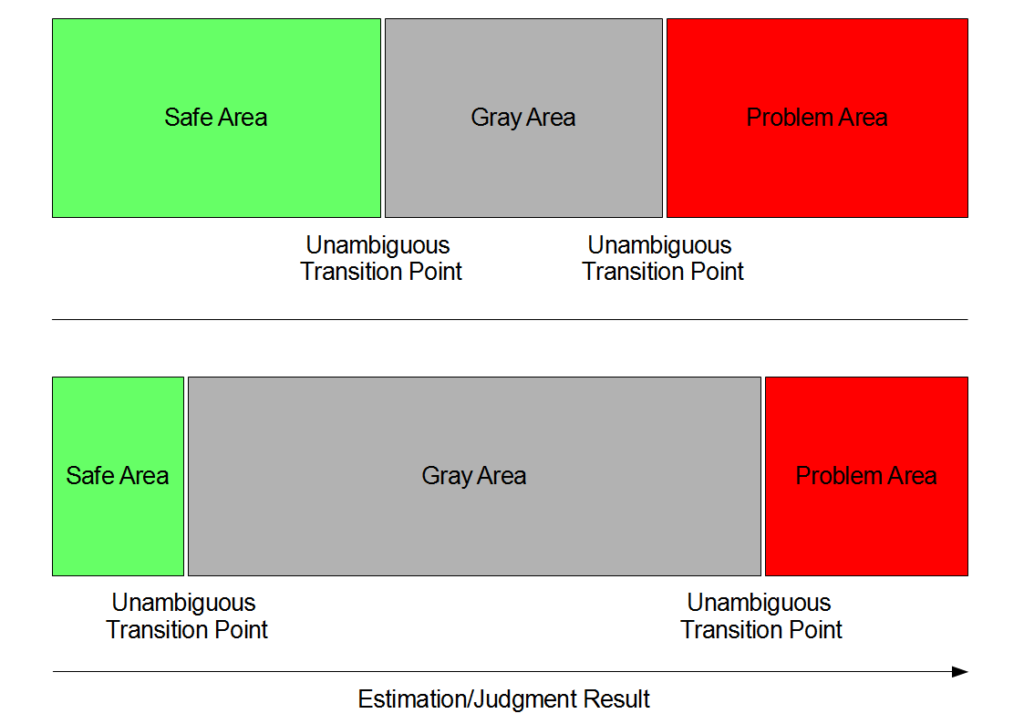

In regards to the reliability of humans, let’s prime this discussion with a picture:

The idea is nothing you haven’t heard of before; when you are faced with a control problem, you want to intervene when your estimation of the situation approaches the point where you no longer have confidence in your assessment of safety.

Naturally those thresholds will vary based on the process you are controlling. However, in the case where humans are involved, the sources of variation tend towards making a large gray area and typically very few enduring safe areas for the most serious risks.

If a human fails, why is that?

– Heart attack or other incapacitation

– Normal human screwups in situations where they would normally make correct decisions

– They changed their mind about what they wanted to do and can no longer be counted upon to execute the process as you drew it up

Of course humans will become incapacitated from time to time; this is why you have co-pilots, automatic takeovers by machinery, fail-safes, monitoring, and so on. If you correctly accounted for these possibilities, you should be able to stay in the safe area.

Likewise for normal mistakes: you know people are going to make them, so you install processes to detect and correct them where feasible. Since the correction of such innocent mistakes is even tractable by showing the responsible party the problem, this shouldn’t push you into the problem area.

Even for changes of heart/lack of motivation, if you are just talking about a few people, this is a normal thing that you can anticipate and for which you can put in place mechanisms for replacement.

Hence the transition into the gray area is typically either:

– You were already there in the first place

– You have few/no effective process controls and oscillate wildly

– Somebody deliberately pushed you into there, and the magnitude of that change went way beyond your existing controls

If you were there already, you have to implement some sort of corrective actions related to the cause. If the cause was lack of effective process controls, you have to install those controls. If that was because of sabotage and subversion, you have to remove those individuals.

Consider more thoroughly the case of effective process controls. Beyond the due diligence measures noted above, what would cause us to judge the process controls ineffective, noting that they would include

– Coaching and retraining

– Replacing responsible individuals

The causes would include

– Not identifying the deviation/move into the gray area

– Coaching and retraining is not effective for the classes of personnel you are recruiting/placing (e.g. because they cannot/will not follow rules)

– You can’t find suitable replacements, i.e. they have similarly bad flaws or weaknesses

Not identifying the problem will be dealt with in more detail below.

If you learn over time that coaching and retraining are not effective, you have to look to machinery, or else restructure the process in a way that the apparently inherent human failure can be mitigated, or perhaps you can raise salaries and perks to attract coachable individuals.

If you cannot find suitable replacements, or, you think you are finding suitable replacements and they fail anyway, you have no choice but to restructure the process entirely to avoid creating whatever dangerous condition is being so heavily compromised.

The first policy to improve the effectiveness of identifying deviations is full transparency, and corrective action, i.e. replacement, if you see people hiding or attempting to hide things.

Consider the case where the actions of a single individual can move you all the way from the safe area into the problem area at the push of a button. In this case, the coaching and retraining or replacement are ineffective, for your detection process isn’t going to move fast enough to prevent catastrophe. More generally, you can look at this situation and state that if your detection process operates more slowly than individuals’ ability to transition you from the safe zone to the gray zone, and/or the gray zone to the red zone, it doesn’t matter what your corrective actions would be. Adding detail, your detection process must be able to fix on deviations early enough that your corrective actions (assuming they will be effective) have enough time to work and get you the result. These lags extend the effective gray zone.

From a mechanical perspective, this means that the responsible individual has to take an action or say some words, then you have to observe those things, then you have to pursue corrective measures. In the case of honest mistakes, this is pretty easy to fix, you just have to have some slack and double-checking. However, if the individual is malicious, they won’t accept your coaching and won’t go willingly. Furthermore, if they hide their actions and stonewall you, you won’t be able to observe the transgressions in order to implement the corrective actions. Hence the normal supervisory observe and correct is completely defeated in the case of malice. In the case of high risk, this dynamic again extends the effective gray zone.

Therefore, when the gray zone becomes wide relative to human performance, then the only effective means of control is installing reliable people – but you understand that is “begging the question”/assuming the outcome. Then the focus of improved reliability turns to cultivating reliability in people, and getting rid of the unreliable ones. This implicates an issue known as the “succession problem”: when individuals are progressively placed in positions of greater power and influence, their rational incentive to conceal their unreliability is proportional to the gains to be achieved from promotion. In the end-state of an absolutist system, where an individual gains control of an enterprise or a government and has absolute power, ambitious individuals rationally would hide any self-interest until the moment at which they gain absolute power, and then become completely unreliable.

Hence at all levels, when people may be able to hide or tamper with your management observables, the recommended technique to assess reliability is the sting operation. However, certain actions, such as major strategic decisions, can’t effectively be evoked via a sting – this only applies to routine cases or bribery situations where an individual can be subjected to influences within their normal job scope. A re-education session or fake assignment can only be of limited effectiveness because the ambitious and wary individuals will attempt to mirror the attitudes and behaviors of their superiors; if they truly are given a blank slate, with no clear example to emulate, then the issue becomes whether their failings are the result of insufficient expectations, or their ulterior motives/unreliability.